New drug could help treat neonatal seizures : Researchers

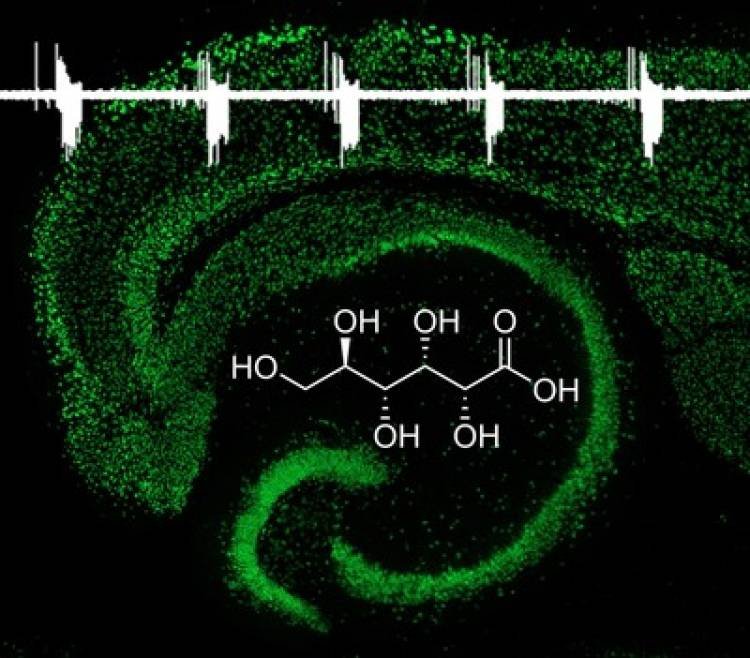

A new drug that inhibits neonatal seizures in rodent models could open up new avenues for the treatment of epilepsy in human newborns. Researchers have identified that gluconate a small organic compound found in fruit and honey acts as an anticonvulsant, inhibiting seizures by targeting the activity of channels that control the flow of chloride ions in and out of neonatal neurons. A paper describing the research, from an international team of scientists led by Penn State researchers, appears May 15, 2019 in the journal Molecular Brain.

“Neonates are the most vulnerable population to seizures but there is still no effective medication for the treatment of neonatal epilepsy,” said Gong Chen, professor of biology and the Verne M. Willaman Chair in Life Sciences at Penn State and the leader of the research team. “The incidence of epilepsy is highest in the first year of life, with two to four infant babies suffering from neonatal epilepsy for every 1,000 live births in the United States. Unfortunately, so far there is no effective drug available that is specifically developed for neonatal epilepsy patients.”

Over the past decades, many drugs have been developed to treat epilepsy in adults. However, neonatal epilepsy patients are often resistant to or do not respond to current anti-epilepsy drugs, and long-term use of some of these treatments may have side effects on brain development. In the current study, Chen and his colleagues demonstrated that gluconate can inhibit seizure activity in neonatal neurons. More importantly, gluconate suppresses seizure activity in neonatal animals more effectively than in adults.

Gluconate, a small organic molecule, inhibits neonatal seizures in rodent models and could open up new avenues for the treatment of epilepsy in human newborns. The image illustrates the structure of neonatal hippocampus (green), overlaid with a typical electrophysiological trace of seizure activity, and the molecular structure of gluconate. Credit: Chen Laboratory, Penn State

“This is truly exciting because we have finally identified a potential anticonvulsant drug that shows preference to inhibit neonatal seizure activity,” said Chen.

Gluconate is already widely used in the food and pharmaceutical industries as an inactive food or drug additive. For example, it can bind with metal ions to form stable gluconate salts, such as calcium-gluconate, potassium-gluconate, and zinc-gluconate, that are used for the uptake of metal-ion supplements.

“Gluconate is a small organic compound that is produced through the oxidization of glucose in many plants, fruits, and honey,” said Zheng Wu, an assistant research professor at Penn State and the first author of the paper. “It has minimal side effects when compared to other organic ions. Because of this, our discovery of its anti-seizure function in neonates could have an accelerated path toward therapeutic development for use in the treatment of neonatal epilepsy.”

The research team found that gluconate inhibits neonatal seizures by targeting what are known as CLC-3 chloride channels. These channels mediate a large ion current in neonatal brains but are less active in adult brains. Gluconate appears to be too large to pass through the small openings of the CLC-3 channels and therefore acts as a channel blocker.

“We were surprised that gluconate targeted CLC-3 chloride channels because they have been associated with regulating neuronal transmission, glioma proliferation, and neuron cell death, but until now, there was no mention of neonatal seizure at all,” said Wu. “Here we found not only that CLC-3 chloride channels are highly expressed in the neonatal brain but also that they are closely related to neonatal seizures. Importantly, gluconate not only blocks the CLC-3 chloride channels but it also significantly inhibits neonatal seizure activity. Its neonatal activity makes it a great specific target for neonatal anti-epilepsy drugs.”

In addition to gluconate, the research team also showed that a ketone body called β-HB, which is generated in the liver under a ketogenic (low-carb, high-fat) diet, can also act as an inhibitor of CLC-3 chloride channels and suppress neonatal seizure activity. In fact, ketogenic diets have been used to control some childhood epilepsies, but often with unwanted side effects in a small number of children.

“The similar effects of gluconate and a ketone body in inhibiting both CLC-3 chloride channels and neonatal seizures may suggest a better treatment than a ketogenic diet in suppressing neonatal seizures,” said Chen. “Our studies not only identify a new drug target, the CLC-3 chloride channels, for neonatal epilepsy but also discovered two potential anticonvulsant drugs, gluconate and the ketone body β-HB, that can suppress neonatal seizures. Our work also opens a new avenue for other scientists to design even more specific and potent blockers for CLC-3 chloride channels to treat neonatal epilepsy.”

In addition to Chen and Wu, the research team includes Fengping Dong, Mengyang Feng, Yue Wang, Yuting Bai, Gangyi Wu, and Bernhard Lüscher at Penn State; Qingwei Huo and Cheng Long at South China Normal University; Liang Ren and Yun Wang at Fudan University, Sheng-Tian Li at Shanghai Jiao Tong University; and Guan-Lei Wang at Sun Yat-sen University. The research was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health and the Charles H. "Skip" Smith Endowment Fund at Penn State.